As noted elsewhere on this site, the current main bus station in Prague, Praha-Florenc, is scheduled for relocation at a notable distance from its current site, behind the literal ramparts of two main rail lines: the Negrelli Viaduct heading to the north and the earthwork of the primary rail link from Prague eastward. The reason is to allow the private-equity firm Penta free rein in constructing profit-generating real estate where the platforms and parking areas of the bus station once stood.

Penta currently holds as its private property a significant chunk of land in central Prague associated with transport infrastructure, acquired with little political debate and nearly no public involvement. The current flagship realization is the gilded “radiator“, or for others the “needle-on-the-record“, of the massive Masaryčka office complex, conventionally attributed to the Zaha Hadid Architects studio. While controversy certainly exists as to the degree of authorship by Hadid herself (who died in 2016), it is worth recalling how the current principal of the enormous firm, Patrik Schumacher, is notorious for his inflammatory techno-libertarian appeals to “pave Hyde Park” and abolish social housing….

But enough about the increasing spread of future necrotechture through central Prague. In the face of crushing overtourism, is the addition of more corporate Sim-City-knockoff-scape the very worst threat? No, the important task at hand is, instead, to undertake a considered critical appreciation of the Praha-Florenc bus station as it is, the bus terminal as a crucial socio-spatial typology for 21st-century Europe, and the role of non-places (or should we say “placelessness”?) – for good and ill – in the migratory societies of the present and future.

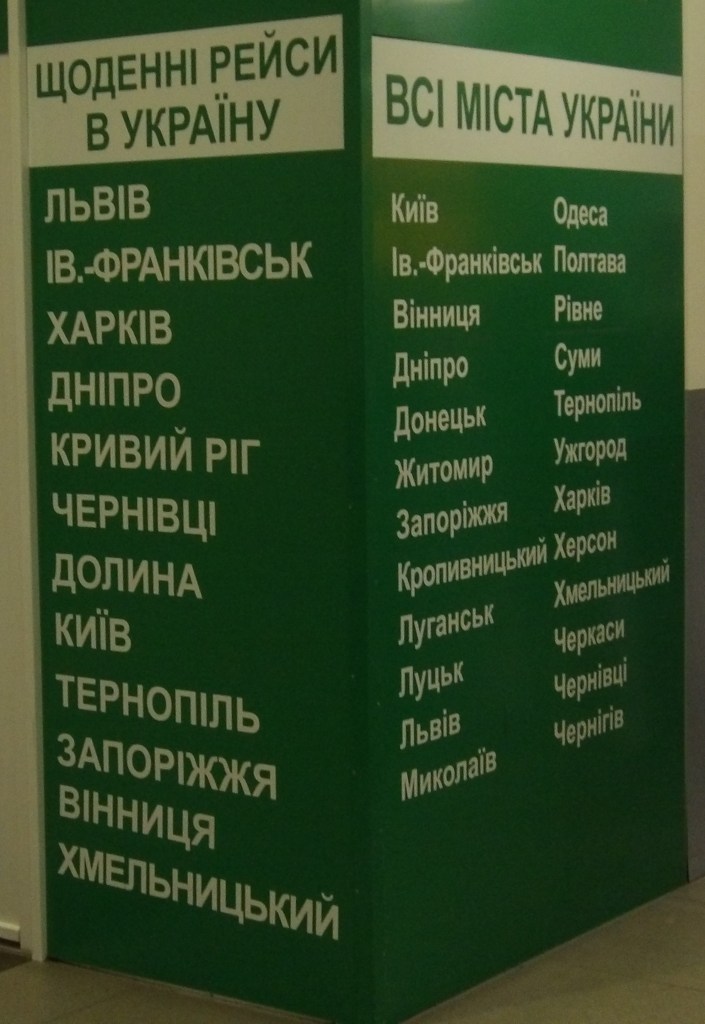

Even before Russia’s unprovoked aggression against Ukraine, in other words before the blue-and-yellow flag and the trident became a universal symbol throughout Czech society, I found Florenc bus station a vital urban locus: indeed, a kind of inland port bringing the city into a continent-wide network of transport flows far different from its air or even rail links. And like any port, it reflects the world from which the arrivals come – in this case, Ukraine as an exploited Czech hinterland.

Yes, as a Benjaminian dialectical image revealing how a metropolis draws in the very workforce that keeps it operating, from construction to manufacturing to services, Florenc bus station forms an uncomfortable moment for the metropolitan classes, reminding them of how precarious, in short, their comfort is. But as with all loci of immigration, Florenc is simultaneously a point of sorrow and of triumph, of loss and achievement.

The Anglophone world has its specific points of migration-memory, from the docks of the great port cities to the trunk of a Chevy passing through San Ysidro. For continental Europe, by contrast, the main coordinates in the migration vectors have shifted from the rail station precisely toward the cheaper, more flexible bus terminal. Moreover, the twentieth century – where rail transport could imply at best the bittersweet promise of exile, at worst prison camps or outright genocide – casts no poisoned shadow over the flux of bus-based migration. Which, of course, is not to say that events of the future could not prove still worse….

Almost certainly, Florenc bus station will persist in both collective and family memories of the Czechia now in formation: mobility spaces have a way of integrating themselves into historical narratives, if most often when they have been superseded by another space and another migration. The contempt evident in current public discourse on the station, even beyond the Penta plans for its displacement, is only evidence of its vitality – no Ellis Island museum here, no comforts of nostalgia. In the face of the harsh rejection, the twinned xenophobia and classism displayed by Penta’s objectives, there is a strong temptation to praise the bus station along with the European bus system as a laudable institution, indeed one deserving of EU honours. Yet no less immediately, the typology of the bus terminal is itself ambiguous: a deliberate non-place that only reinforces the placelessness of migration as a human flow.

For after all, any architectural form devoted to the motor vehical brings with it the place-wrecking force of the automotive road: the vertiginous “Autopia” of movement at all costs. Again in contrast to the monumentalism of the rail station, the bus terminal is itself an emptiness – empty platforms, the anomie of the parking lot. Nor is it to mention the situations where a bus station has literally scraped bare a worthwhile section of urban tissue. Even within Prague itself, not too far distant, lies the blank asphalt gap of the former Palmovka bus terminal for inner-city connections, slicing through the historic suburb of Libeň in 1988 only to be replaced just over a decade later, as the metro forged eastward, by the current station at Černý Most.

And from another standpoint, the bus station is a point of “embodiment”: of the reduction of its human passengers into their mere bodily form, as the subjects of the economic order putting them into motion. Here we should recall how so much of the migration to ensure the day-to-day functioning of Czech life has historically been cyclical, confined to short-term contracts, one-year visas, hot-bedding in disgusting workers‘ hostels. Wages that would never allow for ascent onto the proverbial housing ladder. And the prospect of returning home, as the expected end, along the bus routes eastward. A space of placelessness, yet equally one of de-homing, of an “Unheimlich” where the threats are less the unspoken phantasms of Freudian interpretation but the all-too-concrete visa authorities, supervisors, police, bedbugs….

A dialectical image across multiple levels: hopeful, tragic, built, empty – and above all else, revelatory, exposing the hidden injustices of movement in the 21st century, and the hypocrisy of Czech society in ignoring how a de-homed labour force has been placed precisely at the heart of the national economy. Hard to appreciate, yet calling for our attention. Perhaps at the specific, irrepeatable, “owl-of-Minerva” moment when its destruction immediately threatens, most evidently demanding that we appreciate its visible, invisible, or even unwanted qualities.

Leave a comment